"Cultivating Pasadena began life as a public exhibit at The Pasadena Museum of California Art, expanding multimedia into several tactile, sensory and spatial dimensions via the contours of immersive installation. That version of the project generated a lively response, igniting as it did countless reflections and narratives from museum visitors about their own recollections of the history and development of the city of Pasadena. Portions of the project have been extended indefinitely at the museum and, as such, Cultivating Pasadena maps important new directions for the public humanities, illustrating timely transit routes between scholarly considerations of historiography, memory, and the database and public engagements with those same terrains. We've here excerpted one section of the DVD-ROM that was produced following the museum installation, one focused on transportation in Pasadena's development, an appropriate selection given our theme of 'mobility.'

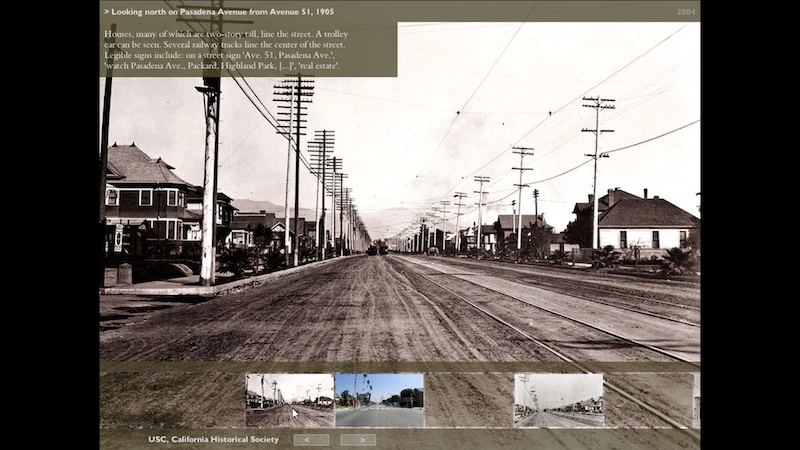

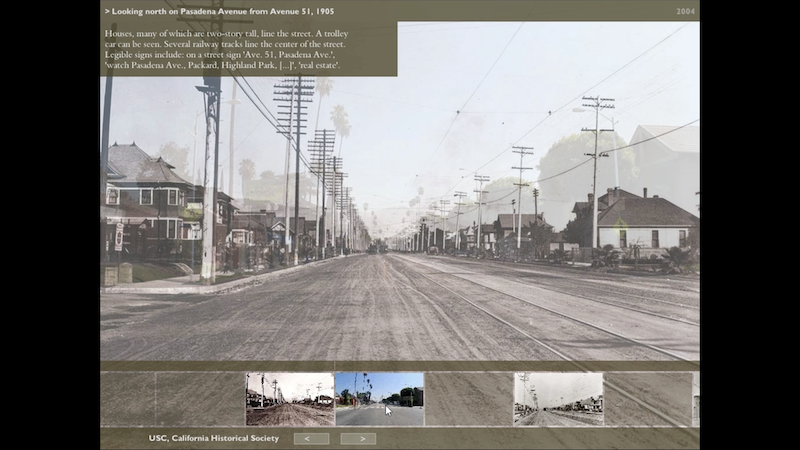

'Transportation' intersects with issues of mobility in some fairly obvious ways, particularly given the status of Southern California as a region that 'came of age' with the automobile. But Cultivating Pasadena tracks mobility along other, less literal, trajectories as well, particularly in its brilliant use of 'rephotography,' charting both the mobility of the city across time and the mobility of memory and pleasure, especially as these are scaffolded by the work of the image. In courting speculation about the space between the 'before' and 'after' images, the project invites the user to imagine other Pasadenas and other histories, including histories of loss and displacement.

Labyrinth Director, Marsha Kinder, describes one subset of the collective's work as 'database documentaries,' inventive multimedia projects that create a hybrid space where theory and practice collide. Drawing from cinematic language, they push these grammars toward new intermedial potential, crafting project after project that beautifully blend form and content, technology and theory. In many ways, the pioneering effort of the Labyrinth Project helped to create the space from which Vectors might emerge, and we are pleased to be able to present this sample of their work. It raised for us interesting questions about the status of the 'excerpt' in the digital age, for selecting a portion of a digital project for reproduction is not the same as publishing a chapter of a book. Nonetheless, much as a book chapter functions as a lure for the larger project, we hope that this selection from Cultivating Pasadena encourages you to learn more about the Labyrinth Project." – Vectors Journal Editorial Staff

Designer's Statement

"Pasadena: An Experiment in Time Travel

– Rosemary Comella, Creative Director/Designer

If the old adage 'a picture is worth a thousand words' holds true, then perhaps two pictures of the same place taken decades apart are worth exponentially more, for they offer us insights into a community's development in a particularly visual way. The exhibition phase of Cultivating Pasadena explored this premise, dramatizing the city's development from the end of the 19th Century to the present. The exhibition and its components functioned as an interactive time machine not only featuring 'then and now' photographs but also presenting historians, experts and 'aficionados' including Claire Bogaard, Lee Silver, Kevin Starr, Karen Stokes and Robert Winter speaking on topics ranging from architecture, freeways and geography to culture, race and community. This material was exhibited at The Pasadena Museum of California Art through a transmedia network that included a large screen interactive projection, printed catalog and 25 pairs of 'before and after' photographs. The excerpt displayed here, as part of Vectors, is a sample of an extensive DVD-ROM produced in conjunction with the exhibition. Currently, the Labyrinth Project and the Pasadena Museum of California Art are proposing a second phase for the project that will expand its interactive potential and degree of community participation. This second phase, Cultivating Pasadena II: From Personal Stories to Homegrown History, will be built around the community's contributions and responses to the city as it is and the city as it was--personal histories and collections entwined with a collective past. Residents, preservationists, enthusiasts and schools, among others, will be invited to collect oral histories, photographs, home movies, and memorabilia for another exhibition and website.

The following is a description of the production of Cultivating Pasadena: From Roses to Redevelopment

Cultivating Pasadena stems from an earlier digital project, entitled Bleeding Through Layers of Los Angeles, 1920-1986, that simultaneously investigates the history of downtown Los Angeles and the nature of storytelling itself.1 While both projects involve rephotography, Cultivating Pasadena relies more heavily on this practice as a way of chronicling the evolving urban landscape. In the course of showing Bleeding Through to audiences, my co-creators and I noted that the digital cross-dissolves between vintage archival photographs and contemporary color views of the same urban scene elicited particular pleasure. This project is, in part, a response to that reaction and further inquiry into its cause.

What is the source of this pleasure? Perhaps it is because in one visual moment we solve one mystery as another is uncovered. Now that we know what the site looked like from one point in time to another, are we then compelled to imagine how and why a site has changed so drastically or so little? What are the forces that transform a site from rural to urban, from well-tended and occupied to neglected and abandoned, from Victorian to modern? And what are the forces that keep something preserved?

As one of the photographers on the Bleeding Through project, I began to think of rephotography as a form of time travel linking one point in time to another. It is also a form of time-lapse photography, demonstrating the passage of time while remaining in the same place, revealing cultural and physical changes that we may otherwise never see. More profoundly it demonstrates the existential nature of space and time - the disappearance of memory, the impermeability of things.

Selecting the images to be rephotographed can be a challenging undertaking, particularly when trying to encapsulate the major characteristics of how a place developed over time. When I first browsed the on-line collection of the Automobile Club of Southern California looking for archival images of downtown Los Angeles for Bleeding Through, I was struck by how such mundane intentions, the documentation of road safety or traffic conditions, had often resulted in capturing something sublime. While a pristine Ansel Adams photograph of the moon over Half Dome demands that we view it in a particularly romantic way, the Automobile Club images had a refreshing unselfconsciousness. They provided a seemingly unadulterated look into the past that caught the unposed, the spontaneous, the inconsequential details that lend authenticity to a scene. In rephotographing Pasadena, we again returned to the collection of the Automobile Club (now our collaborators), looking for such representations of the city's past.

This search proved more difficult than our team (Matt Roth and Morgan Yates of the Automobile Club and Marsha Kinder, Karen Voss and myself of the Annenberg Center) had first imagined. Now, rather than simply looking for something intangible that expressed the feel of the street, we needed a broad range of images that would chronicle Pasadena's unique development. While the Automobile Club's collection is stunning in its quality, its focus on transportation and planning necessitated that we explore additional archives - such as those belonging to USC, the Pasadena Museum of History, the Los Angeles Public Library, Caltech, and finally the California State Library - in order to represent other themes. As the prints were to be exhibited, we looked for archival photographs that contained fine detail and a wide tonal range. In some cases, however, this technical prerequisite was overridden by the desire to retain images that contained significant traces of the past - early prints so many generations removed from their original negative that they simultaneously preserve and erase the past. Although the selection process was methodical, a number of factors made it somewhat arbitrary - which archives we were able to access, how much time and money we had, the limitation on the number of prints to be exhibited and last but not least our personal aesthetic preferences. Thus the final selection of twenty-five pairs of photographs is far from exhaustive.

The next step in our process involved a combination of detective work and location scouting, for the selection of images had to be narrowed to those sites we could re-find.2 We followed clues - the name of a residence, street names, a recognizable geological area, or urban landmark. Often, Lian Partlow, archivist from the Pasadena Museum of History, or some longtime resident, offered invaluable assistance in identifying a depicted site. Once we had a probable location, I then went there to take a series of digital shots that we would use to determine if it was indeed the correct location, and if it should be included as part of the exhibition prints. Some sites, I could not verify. Sometimes I sought out several photographs of the same site to help figure out, for example, whether a disappeared mansion sat facing Orange Grove Avenue or was set back from the road. I took many more photographs than would be included in the final twenty-five pairs, in part, because I was curious. Many of these additional images are included in the interactive DVD-ROM.

Rephotography is an idiosyncratic way of getting to know a locale, a little like playing detective or archaeologist. What will be uncovered? A crime scene (in which something beautiful has been replaced by something hideous), an act of preservation, an improvement, or just a progression? Along with the challenge of simply finding the locations, these questions drove me out into Pasadena, day after day. Looking at so many images of Pasadena throughout its history was like trying to get acquainted with someone by paging through their family albums. After I had walked the streets and highways, entered buildings, climbed around the Arroyo, discovered the obvious panoramas, and met people from the Pasadena area, little by little, our selection grew and changed.

Discovering more than 3,000 photographs by Frederick Martin in the California State Library collection, mostly depicting the San Gabriel Valley, also changed our selection. Well-composed, straightforward photographs taken between 1910 and 1930, they document much of Pasadena's landscape and architecture. Their sheer volume is compelling. Now not only did I speculate about Pasadena's past but also about Martin's reasons for thoroughly documenting so many of Pasadena's houses and gardens. According to Gary Kurutz, photography archivist in charge of this collection, little is known of Martin except that he settled in Pasadena at the turn of the century and began working for Kohler Photo Studio on Colorado Boulevard in 1902. He later took over the establishment, renaming it the Martin Studio. Martin died in 1949. Six of the photographs in the exhibition and book are by Martin, and many more of his images are found in the DVD-ROM.

After the digital scouting, I began the analog photography using either a 4 x 5-inch large-format camera or a 6 x 9-cm medium-format camera. During these sessions, if the situation permitted, I tried to take my photograph at approximately the same time of day and from the same point of view as the original but using color film. (Rephotographing in color works well for cross-dissolves because it gives the viewer enough distinction between the archival and contemporary images to perceive where one begins and the other ends.) Street-widening and incredible tree growth made precision difficult in reconstructing some shots. At certain sites, little if anything of the original composition remained. For example, the Carr House and its surrounding Carmelita Park are now the location of the Norton Simon Museum. Although it was difficult to situate the Victorian homestead precisely, the transformation of a site created by one of Pasadena's early cultural patrons into a modern art museum suggests thematic continuity. In place of the once-massive Moorish-themed Universalist Church, a lone palm tree now stands, its trunk echoing the disappeared church tower.

In rephotographing an early agricultural landscape taken from Monk Hill featuring the San Gabriel Mountains, I shot a wider view, letting the playground of Washington Middle School occupy more of the frame. In changing the framing I hoped to expand the notion of rephotography from an exact science for measuring physical changes to an interpretative tool for examining such cultural phenomena as land use and urban development. Showing what is beyond the periphery of the original view is one way to contextualize the images. That intention motivates Karen Voss's essay, Cultivating Pasadena, and is a primary aim of the interactive DVD-ROM. Designed to be a kind of 'vision machine,' the DVD-ROM not only performs the cross-dissolves but also provides the viewer with other materials from our inquiry that might enrich the comparison between past and present. It includes the videotaped interviews of Pasadenans, quotes from experts and 'aficionados,' as well as excerpts from period films and contemporary videos. From these multiple visual and intellectual perspectives on Pasadena's development, viewers can pursue their own investigations, driven by curiosity and chance.

During my exploration of Pasadena, I encountered many knowledgeable people who were eager to help me uncover, in the contemporary landscape, the original views found in these archival photographs. Quite by accident I met Tim Brick of the Arroyo Seco Foundation, whose website I had been exploring (www.arroyoseco.org.) He was walking his dog along the Arroyo and wondered whether I was photographing an Oak tree that the city wanted to cut down. Some were protesting its destruction. Actually, I was trying to figure out the vantage point of a turn-of-the-century photograph of the Arroyo Seco before the Colorado Bridge was built. He joined me in searching for this view and told me where I could find other photographs of the Arroyo.

In trying to locate one amazing Gothic-looking mansion dating from the turn-of-the-century, which I deduced had been located near the intersection of Pasadena and Arlington Avenues, I met a tenant in a house owned by Caltrans. She explained that Caltrans owned her unrestored home (a rarity in Pasadena) and all the others in that historic neighborhood due to a right-of-way battle to connect the 710 to the 210 Freeway. This battle had been going on for more than fifty years. On a subsequent visit, I met another woman who actually remembered the mansion, telling me precisely where it once stood and of its deterioration into an eerie run-down place that frightened the neighborhood children, including her. I went repeatedly to Washington Middle School, drawn by its fabulous location on Monk Hill. Teachers, custodians, administrators, and vice-principal, Robert Tanous, allowed me to use the windows and roofs of their buildings as lookout points from which to make photographs. There I stumbled upon one landscape view that I had been hunting for days: the setting for the original Washington School, built in 1884 and now gone. This school on Monk Hill came to symbolize for me the future of Pasadena, as a harmonious and ethnically diverse population nestled within a stunning landscape.

While searching for the site of reputedly the first house built in Pasadena in February 1874, by early founding father Albert O. Bristol, I met Frank Burkard, Sr., of Burkard Nursery. We surmised that his nursery, on the southwest corner of Lincoln and Orange Grove, is located next to where the Bristol 'honeymoon cottage' must have stood. Although Burkard did not recall the cottage (pictured in our book), he did remember the Victorian house that Bristol had built next door in 1888. The cottage burned down in 1936 (a year before Burkard's father opened the nursery) and the Victorian house, of which I could not find a photograph, was most likely torn down in the late 1960s. In its place is a commercial complex that includes, among other community services, the NAACP. There I met Janet Akosua Edge, a charter member of the branch in Altadena since 1984, who also grew up in this neighborhood. Her recollections begin around 1957 when this part of North Pasadena was a self-contained African-American enclave with its own caterers, churches, childcare, library, barbershops, mortuaries, parks, schools, and stores. The dismantling of this large, closely knit community coincided, she felt, with the construction of the Jackie Robinson Center built in 1974 on the east and west sides of North Fair Oaks. Presented as a benefit to the community, she sensed it was really a diversionary tactic that allowed developers to maneuver long-time residents out of their bungalows, cottages and Victorians in preparation for further improvements that never materialized. She graciously agreed to be interviewed about this neighborhood for the Cultivating Pasadena project.

Many residents were especially accommodating. Volunteer gardeners at the Lummis house trimmed away foliage from a tree so that a little more of this stone masterpiece could be captured. Two residents above Devil's Gate Dam allowed me to wander their property several times looking for just the right view. While scouting Bungalow Heaven, one interested owner on Claremont Street suggested the best of Martin's images to rephotograph was the bungalow with the children in front of it, two doors down. When I asked to photograph the famous Blacker House, its owners Dr. Ellen Knell and Mr. Harvey Knell, who are inundated with such requests, kindly agreed.

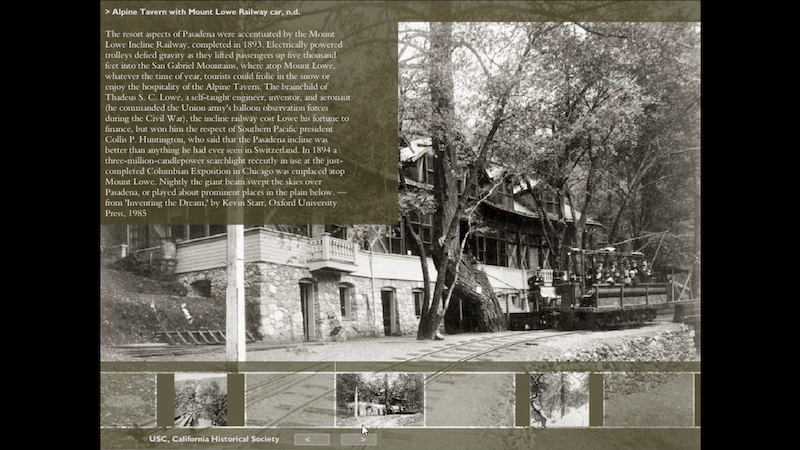

We also sought out people. Dennis Crowley, a historian and bike enthusiast who is leading an effort to rebuild a modern version of the Horace Dobbins Cycleway, helped me locate his favorite photograph of this raised wooden cycleway and took me to the top of the Green Hotel so I could photograph the place where it once stood. John Harrigan, volunteer park ranger for the U.S. Forest Service, scouted one image of the Mt. Lowe Cable Car for us and, in mid-April, took Morgan Yates and me up to Granite Gate in the San Gabriel Mountains to take a large-format view of it. This spectacular trip was made more memorable by Harrigan's enthusiasm: he pointed out plants in bloom along the way - ceanothus or 'California lilac,' wild hyacinth, rose, and wishbone bush - and characterized Mt. Lowe's railway as a tourist attraction made compelling not only by its miraculous engineering but also by the breathtaking views and dizzying heights 'that would still surpass any thrill-ride found at Disneyland.'

While exploring Pasadena with these knowledgeable, enthusiastic residents, who helped transport me back in time, I often reflected on how to best convey the experience of these encounters within the actual physical environment. It is my hope that the DVD-ROM with its 'bleed-throughs' and commentaries will enable viewers to move between past and present and to navigate this space as a journey through time, and that this excerpt will inspire you to seek out the larger project.

_____________________________

1 Bleeding Through was produced by the Labyrinth Project and ZKM (Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe) in collaboration with writer and cultural historian Norman M. Klein. Directed by Rosemary Comella, Norman M. Klein and Andreas Kratky.

2 Many people participated in this effort, including Matt Roth and Morgan Yates of the Automobile Club, Scott Mahoy of the Labyrinth Project, Sirirat Thawilvejakul-Yoom of USC's School of Cinema-Television, and Meredith Drake-Reitan of USC's School of Policy, Planning, and Development, as well as students from an experimental summer workshop at the Labyrinth Project called 'Interactive Narrative: Theory and Practice.'

— The Labyrinth Project" -- from Vectors, Volume 1, Issue 2, Spring 2006

Writer-Researcher's Statement

"Cultivating Pasadena: From Roses to Redevelopment (excerpted from the original catalog copy)

– Karen Voss, Writer/Researcher

Pasadena history can unfold in a series of intoxicating landscapes – if viewed from certain vantages. Imagine arriving in Pasadena for the first time in the late 1880s as a wealthy Easterner, when you would have been dumbstruck by the aroma of blooming poppies and the majesty of the San Gabriels – in the middle of winter. Imagine picking oranges year-round. Imagine a sprawling, blooming rose garden on a private estate – not as the owner but as the one who worked it and lived in a tent. Pasadena's unique reputation for horticultural splendor and technological adventure is reinforced each year as the Rose Parade unfurls on New Year's Day. It is also reinforced in the names and courtyards of its civic monuments, landmarks, and achievements. From the Rose Bowl to each year's new, genetically engineered rose displayed in the garden beside the Wrigley Mansion on Orange Grove Avenue to the Mars Rover originated at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory – this is brave terrain. But this is not all there is. In many ways, Pasadena history reveals striking superimpositions: robust oranges photographed against snow-capped peaks; lavish private estates maintained by a shadow workforce; and scientific progress pursued as zealously as wilderness preservation.

In selecting images for this project, we wanted to reveal as much of this history as possible while simultaneously emphasizing the complexity of capturing the complete historical record in photograph or text. Ultimately these photographic 'befores' and 'afters' should provoke as many questions as they answer. The nexus of forces that make a city, change a city, brand it with a particular reputation, open it up to a new era of redevelopment are complex and slippery. While informed by prolific historical texts, local publications, walking tours, and word on the street, the final Big Picture will always remain just outside our grasp. To invoke as much 'history' (both what's been preserved and what's missing), however, we have [in the larger project from which this piece is excerpted] organized the photographic couplings around broad categories of recurring civic processes – initial acts of colonizing, landscaping, installing transportation, developing the city and canonizing its landmarks.

Neither mutually exclusive nor exhaustive, the categories should suggest vantages, each prompting different angles and focal points. Some of the image-pairs suggest epic narratives. Some don't. Some pairs align with the historical record. Some imply much is missing. All are involved, however, in a series of complex processes that have made cities in Southern California start, grow and change.

Pasadena history, in particular, is a strange landscape to grasp fully, both physically and culturally, in terms of how it looked in the beginning and what successive populations did with it. As historian David Lowenthal puts it, 'the past is a foreign country,' strange chronologically, culturally, and spatially, Pasadena's especially so. As one of Southern California's oldest enclaves just beyond the pueblo of Los Angeles, Pasadena's formation, growth, and reluctant acceptance of cityhood coincided with the rise of American recreation, 'leisure activities,' and souvenir photography. When the Auto Club generously opened its photography archives, allowing glimpses of earlier, seemingly open vistas with citrus outposts, it became clear that one way to tell the history of Pasadena was to tell it in the opposite way that city histories are usually told. For Pasadena is the result of a succession of land subdivisions (big pieces of land cut up into increasingly smaller parcels) more than it is the result of a master plan.

From San Gabriel Mission territory to the orchards to the resort destinations to the concept of private property, the spaces of Pasadena filtered down through inconsistent layers of imported cultural ideals, speculative land ownership and the collision of native, migrating and conquering populations. What follows should expose as much of Pasadena's history as it does about the complex forces of cultural, political and topographical change that frequently go unnoticed. Spatial choices represented in the photos — from the subdivisions of 'open' mission territory to exploiting horticultural opportunity to building fantasy estates to zoning landmark districts — are important indicators of civic maneuvering in Pasadena. These processes built a city and simultaneously sustained an anti-urban ethos. Ever ambivalent about fully embracing urbanism, Pasadena represents Southern California's most sustained attempt to adorn the Machine with flowers.

The Rose Parade, and the annual building of colossal floats (one of Pasadena's most globally famous endeavors), is just one embodiment of Pasadena's particular mélange of exotic horticulture, competition, technological showmanship, and decorative nature display. How did it happen? How did it get this big? It started with bragging. On January 1, 1890 Pasadena's Valley Hunt Club (men on horses with bugles and dogs) decided to host a winter procession of flower-laden horses and carriages, eventually formalized as the annual Tournament of Roses. In addition to escalating spectacle, the message meant to flow eastward from Colorado Boulevard to the snow-laden Midwest was: Why deal with seasonal discomfort when we've got a bed of roses in the dead of winter? Mansions lining Orange Grove Avenue, one of the parade route's main arteries, bore the names of magnates such as Wrigley, Busch and Gamble. Lavish resorts, an incline railway, ostrich farms, and an elevated cycleway to connect Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles, were similarly meant to communicate a culture of splendor and innovation.

But this is merely one of the more familiar historical vantages on the city's past. And just as photographers painstakingly search for the correct spot from which to re-photograph a specific location, so, too, will we mark our particular vantages from which we gauge how the photographic pairs we have assembled invoke Pasadena's complex development over time. The degree to which some locations have changed, even vanished, while others have been preserved, communicates as much about the challenges of capturing the totality of urban history as it does about the sites themselves.

...

Transportation: Progress, Technological Showmanship and Flights of Fancy

In addition to parades and railroads, Pasadenans generally liked a good ride. In keeping with Southern California's overall reputation as a health resort, early visitors hiked and camped prolifically, seeking wilderness. Pasadena's unique geography provided a canvas and enabled a culture for technological experimentation in transportation. As Pasadena evolved from a resort to a residential enclave, the wealthy eventually accepted formalized boulevards, street names and addresses. As Ann Scheid points out, the development of specific boulevards and civic axes can be overlaid with the old borders of the missions, many of which in turn coincide with natural boundaries such as the Arroyo, river beds and mountains. The natural geography inspired several cultural responses that remain hallmarks of the Western mentality to this day.

New residents who got off the Santa Fe railroad and put down roots, benefited from a series of 'unnatural' acts: building a transcontinental railway, 'reclaiming' enough water to sustain orchards and gardens, and blasting through geologically challenging land (full of rock and seismically active) to build dream resorts. By 1920 Pasadena was served by three interurban railway systems and two transcontinental railroads. As the automobile grew popular, what may have started in exploratory hiking evolved into exploratory motoring. When the Arroyo Seco Parkway was completed in 1940, it was, in many ways, the culmination of Pasadena's penchant for the combination of transport and progressive engineering. Pasadenans accepted what is considered the first freeway in the West, at least in part because this artery of unprecedented proportions was nestled between grassy park areas. Driving the curvaceous 110 through the Streamline Moderne tunnels (if there's no traffic) is a particularly Western delight. And there were precedents.

Pasadena had more than its share of landscape daredevils. Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe – 'Professor Lowe'– was an 'aeronautical enthusiast,' who excelled at balloon travel and reconnaissance, a common method of gathering information before mechanized aviation. Lowe arrived in Pasadena at the age of 55 after he had made and lost several fortunes. In what would become a pronounced tradition of 'scientific showmanship,' Lowe formed the Pasadena & Mount Wilson Railway Company in 1891 to build an incline railway to the top of Mount Wilson. Since it had become common to hike the foothills and gather poppies, Lowe argued successfully to potential investors that establishing a mountain incline with a grand pavilion or chalet at the top of the mountain, along with a colony of private cabins, would make money. After numerous failed attempts at situating the railway, Lowe and partner David J. Macpherson, an innovative engineer, decided to attempt the impossible: build an electric railway up Rubio Canyon that would rise to an altitude of 3,500 feet in about eight minutes. Steeper than anything previously attempted, the railway would be an astonishing engineering feat. The two main 'Opera Box Cars,' named Rubio and Echo, began operating on July 4, 1893 in an opening celebration festooned with American flags and Japanese lanterns. Even though the Mt. Lowe railway looks precipitous in the early photos – hanging from the mountain by the proverbial thread – there wasn't one accident in the forty-four years the railway operated.

No less ambitious was the elevated cycleway begun by Horace Dobbins in 1897. At the time there were an estimated 30,000 bicycles in Pasadena and Los Angeles, and, as Henry Markham Page asserts, 'it is almost impossible to grasp the importance and popularity of bicycle riding in Pasadena.' In fact, a significant body of municipal law at the time detailed how bicycles and horse-drawn carriages would share the right-of-way on public thoroughfares. According to Catherine Karp's pioneering work, the popularity of public bicycling even played a role in the advent of women's emancipation. When Dobbins incorporated the California Cycleway Company, he pitched a conservative estimate to investors: even if only part of those 30,000 bikers used the elevated cycleway once a month at a toll of 10 cents, the enterprise would be exceedingly profitable. Nothing like it had ever been proposed:

The plans called for a ten-foot wide elevated roadway running from a point near the Hotel Green to just west of the Raymond Hill and from there following the Arroyo Seco to the Plaza in Los Angeles. The average height of the road would be about fifteen feet but of course the actual elevation would vary because of the topography of the land and the necessity of maintaining a gentle and even grade. The structure was to be built of wood with a railing of wire. Lights placed every 200 feet would provide ample illumination for those traveling at night. In order to prevent the possibility of its being an eyesore, the entire cycleway was to be painted a pleasing shade of green.

Dobbins' timing, unfortunately, was just off. Bicycling peaked, giving way to rising interest in the 'horseless carriage.' Although the cycleway made it only to a length of 1-1/4 miles, the striking beauty of the idea remains in the tenacity of local resident, Dennis Crowley, who is leading an effort to build a completed version to downtown Los Angeles.

No account of space and transport in Pasadena would be complete without referencing the innovations and the culture of technological optimism associated with the California Institute of Technology, originally Throop University, then Throop Polytechnic Institute, and currently nicknamed Caltech. As Pasadena gradually accrued urban features – a main street, arterial boulevards, a post office, and utilities, among others – the realization grew that it would also have to accrue cultural institutions such as schools, museums and universities if Pasadena's status would ultimately exceed that of an outpost.

By 1904, George Ellery Hale had built the Mount Wilson Observatory, established the new discipline of astrophysics, and invented a number of instruments to observe the stars (celestial, not cinematic). An M.I.T. graduate and member of the Royal Astronomical Society, Hale wanted to open up the heavens. And he just about did it, transforming provincial Throop University into the definitive, global leader for the study of astronomy. Socially and scientifically astute, Hale marshaled sufficient resources to establish The Carnegie Observatories, headquartered in Pasadena, which continue to mount telescopes across the globe to allow for a better look; he also had a hand in building some of the world's most powerful looking-devices, including the 200-inch Hale Telescope.

By January of 1931, Hale had assembled a scientific dream team, including Albert Einstein, in a technological ferment that would 'completely revolutionize our concept of the universe' as well as providing the scientific scaffolding for the atom bomb. A cooperative wind tunnel, completed in 1942 in Pasadena, convened Douglas, Lockheed, McDonnell, Convair, North American and of course, Caltech, to find out everything there was to know about objects at high velocities. Around the same time, Howard Hughes 'skywrote' the outline of Jane Russell's figure over Caltech to promote his film The Outlaw.

In addition to completing numerous scientific milestones, Hale was civic-minded. He convinced Henry Huntington to donate his estate – what would become the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens – to the public good. The Pasadena Civic Center also emerged, in large part, from Hale's participation in the Pasadena Planning Commission.

...

As this exhibit attempts to communicate, the traces that remain of a city's past, whether in photographs or other sources, suggest more than one explanation. They also reveal what has been systematically, or unintentionally, omitted from the official history and mythos. The content of each photo-pair cultivates a series of speculations about the past: why were these images made in the first place, why were they preserved in an archive, and why were they selected for comparison in this exhibition? These questions are purposely left open to some degree, inviting an interactive response from visitors.

— The Labyrinth Project" -- from Vectors, Volume 1, Issue 2, Spring 2006

Producer's Statement

– Marsha Kinder, Executive Producer

"This excerpt comes from a larger project titled, Cultivating Pasadena: From Roses to Redevelopment, a transmedia network (photographic exhibition, installation, DVD-ROM and print catalogue) produced by The Labyrinth Project (in collaboration with the Automobile Club of Southern California). It addresses Vectors' issue of 'mobility' in at least three ways: through the theme of transportation, which is one of the five key topics covered in Cultivating Pasadena; through the horizontal streaming of images that characterizes the interface design of this two-tiered database narrative; and through the transmedia migration of old and new images that move from photography, museum installation, print catalogue, and DVD-ROM, to on-line journal.

Cultivating Pasadena as Database Documentary and Digital City Symphony (from the original catalog copy)

– Marsha Kinder, Director of The Labyrinth Project

How does one spin a web of stories out of archival images depicting a city and weave them together to form a multilayered cultural history of that locale? This is the central challenge in the rephotography exhibition, Cultivating Pasadena: From Roses to Redevelopment. It has also been the driving question for a series of 'database documentaries' that we have been producing (both as museum installations and DVD-ROMs) over the past five years at The Labyrinth Project, an art collective and research initiative on interactive narrative at the University of Southern California's Annenberg Center. But what does interactive narrative have to do with these static pairs of still photographs hanging on the walls of a Pasadena museum? As theorists Lev Kuleshov and Jean Mitry demonstrated in the early days of cinema, as soon as one puts any two images together the combination begins to generate a story. For, no matter whether it is history, fiction, or myth, narrative helps us read and contextualize the meaning of our sensory perceptions and their relations. It makes us understand them within a larger conceptual framework. That is the cognitive function of narrative, which is found in every culture and period and operative within every medium and art form, including rephotography. Yet, in contrast to most other art forms, rephotography strips these dynamics down to their bare essentials. With its paired photographs framed for comparison, rephotography invites or even demands narrative projection. It positions us as active spectators or performers, for it inevitably makes us ask: how do these two images differ, and how did we get from here to there. And, given that these images all depict the same subject--the city of Pasadena and its surrounds -- we begin to select narrative genres whose conventions might assist us in performing this act of interpretative reading: urban history, database documentary, and city symphony.

Two of our earlier database documentaries from The Labyrinth Project also chose a Southern California city as their prime subject: Los Angeles. Tracing the Decay of Fiction: Encounters with a Film by Pat O'Neill is an archeological exploration of the Hotel Ambassador, a 1920 building now in ruins which was crucial to the development of the city's east-west trajectory and to its mythic identification as the capital of film noir and a city of disaster (from earthquakes to the Bobby Kennedy assassination). Loosely based on The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory (1997) by cultural historian Norman M. Klein, Bleeding Through Layers of Los Angeles, 1920-1986 focuses on a three-mile area in downtown Los Angeles, which serves as locale both for a fast-paced detective fiction and an ethnographic documentary on the ethnically diverse populations who actually lived there. Though very different in rhythm and structure, both works show how rival stories and genres (both fiction and documentary) can be generated out of the same database of archival materials. We call them both 'digital city symphonies' -- a subgenre of database documentary that captures and celebrates the distinctive qualities and unique history of a particular urban space. Within a multilayered historical framework, the vintage images, faces, streets, buildings, and interiors are combined with contemporary commentaries and oral histories by cultural theorists and long-term residents of these locales -- a combination also crucial to Cultivating Pasadena.

Every mass medium that has emerged in an urban setting, has generated a new form of city symphony--one that captures the urban rhythms and networked stories that characterize a specific cityscape. It was true of the 18th century English novel, with its picaresque flows between town and country. And it became more prominent in the urbanized context of modernism where the novel's mixed form depicted the distinctive voices, designs and movements of a particular city -- like James Joyce's Dublin, or Andrei Bely's Petersburg, cities which became central characters in their respective fictions. It was true of the early days of radio, where programs like 'Grand Central Station' reminded us that compelling stories could be plucked at random out of this vibrant narrative field. It was true of the early days of television, where local Los Angeles stations like KTLA developed a City at Night format, one you can still find in Toronto, Madrid, Beijing and other major cities throughout the world. And above all, it was true of cinema with its indexical photographic ties to reality and its early mobilization of montage to replicate distinctive urban rhythms. Though this film genre is deeply identified with modernism, its fast-paced repetitions and episodic structures make it a precursor of database narrative. For example, in Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Symphony of a City (1927), one finds (as film historian Charles Musser puts it) 'a relentless cataloguing of urban activities.' In the more radical Man with a Movie Camera (1929), Dziga Vertov literally cracks open the image of his composite Russian city and mobilizes industrial tropes of textiles and editing to weave the fragments back together. Despite their political edge, these modernist city symphonies summarized what was typical about the city--a day in the life--and usually emphasized a particular narrative (about industrialization, Taylorism, alienation, class conflict, or restless energy) that characterized the period as well as the place. Though we have adopted these models for the digital city symphonies being produced at the Labyrinth Project, we must adapt them to the demands of our new cities, media and times.

Today we experience cities themselves as hypertexts; as spatial grids and narrative fields that are deeply enmeshed in highly contested turf wars--whether waged by ethnic communities, street gangs, corporate competitors, conservancy groups, homeowners, real-estate developers, transportation systems, political parties and their rival urban histories. Our cityscapes are narrative spaces we move through looking for encounters, collisions and causality as we race toward random or predetermined destinations. Their stories provide entrance into urban networks that are simultaneously local, regional, national and global, turning cities themselves into database narratives. It is these turf wars over urban and narrative space that we will explore in Urban Traces: Rephotographing Southern California.

As the first exhibitions in the Urban Traces rephotography series, Cultivating Pasadena gave the Labyrinth Project an opportunity to expand and deepen our signature genre of the digital city symphony. This collaboration between USC's Annenberg Center and the Automobile Club of Southern California was first proposed by the Director of the Auto Club Archives, Matthew W. Roth. The Auto Club had already been a key source of archival images for our two earlier Labyrinth projects on Los Angeles, Tracing and Bleeding, as were USC's Special Collections at the Doheny Memorial Library and the Los Angeles Public Library's Photographic Collection, which also provided materials for Cultivating Pasadena. Roth and Morgan Yates (the curator of the Auto Club Archives) and Rosemary Comella and I from The Labyrinth Project agreed that this new collaboration would focus on rephotography and would build on those 'bleed throughs' that lay at the heart of Bleeding Through Layers of Los Angeles. The term 'bleed throughs' refers to a series of paired images of the same cityscape--a black and white archival photograph from the past and a matched contemporary shot in color taken from precisely the same angle by contemporary digital artists Rosemary Comella and Andreas Kratky. (As a core member of the Labyrinth art collective, Comella was the co-director of Tracing and Bleeding, and creative director, photographer and interface designer on Urban Traces). With a simple sliding gesture of the mouse, users could move freely back and forth between these two exposures of the same locale, making buildings, trees and human figures instantly emerge or vanish or (perhaps, even more uncanny) remain remarkably the same. Museum-goers seemed to love this fast-paced navigation through urban history, for it provides kinetic and intellectual pleasures that are rarely combined.

The twenty-five pairs of photographs featured in Cultivating Pasadena can be viewed in at least two ways. They can be seen as a pair of still photographs or portraits (with minimal captions), framed and juxtaposed for the contemplative gaze of viewers, who are free to compare them at their own pace. Or, they can be experienced as fluidly navigable 'bleed throughs' whose dynamic dissolves provide a visceral rush and whose peripheral images and commentaries complicate the basic comparison. While the first mode acknowledges photography's historic debt to painting, the second demonstrates its crucial contributions to hypertexts, animation and database narratives that are defining the digital domain.

Both modes of viewing can be carried back to the domestic space of the home through the print catalogue and DVD-ROM, which feature additional materials and narratives that inspire new responses. One of the richest and most detailed historical readings of the paired photographs is provided by cultural studies scholar, Karen Voss, in her catalogue essay, Cultivating Pasadena, which reminds us of the continuing interpretative power of printed text and which is excerpted here.

Together these varied modes of perception capture the central thematic of the Urban Traces series: the distinctive ways that a particular city negotiates and reconciles two conflicting desires. On the one hand, the desire to preserve what is unique about that city's history or civic identity; and, on the other hand, the desire to anticipate, prepare for and keep pace with the rapidly changing times. This perpetual process of negotiation is the primary subject on display in Cultivating Pasadena: From Roses to Redevelopment.

— The Labyrinth Project" -- from Vectors, Volume 1, Issue 2, Spring 2006

Project Credits

"Direction, photography & design: Rosemary Comella

Executive Producer: Marsha Kinder

Cinematography & editing: Jay Majer

Image development & additional photography: Sirirat Thawilvejakul-Yoom

Research: Karen Voss, Meredith Drake-Reitan, Rosemary Comella, Marsha Kinder, Matthew Roth, Morgan P. Yates

Programming & Sound Design: Kevin Tanaka

Opening Sequence: Sirirat Thawilvejakul-Yoom

Sound: Juri Hwang, Jay Majer

Original Music-Title Sequence: Benjamin Hendricks, Paul Maurer

Additional research: Lin Shi, Ioana Uricuru

Additional photography: Robert Buerkle, Jaime Nasser, Jessica Witkin

Technical assistance: Guillermo Paredes

Advisors: Andreas Kratky, Scott Mahoy

Administration & rights clearances: JoAnn Hanley

Commentators: Enrique Arevalo, Claire Bogaard, Janet Akosua Edge, Lee Silver, Kevin Starr, Karen Stokes, Robert Winter

Special Thanks:

Annenberg Center: Josie Acosta, Steve Adcook, Elizabeth Daley, Janine Fron, Kristy H.A. Kang, Todd Richmond, John Zollinger

The Automobile Club of Southern California: Matthew Roth, Morgan Yates

The Pasadena Museum of California Art: Wessley Jessup

The Labyrinth Experimental Summer Workshop: A transdisciplinary workshop on interactive projects in art &education, 2004

Archivists: Dace Taube, Regional History Collection Librarian, Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections, USC; Carolyn Kozo Cole,

Los Angeles Public Library; Carolyn Garner, Arcadia Public Library; Gary Kurutz, California State Library, Sacramento; Dan McLaughlin,

Pasadena Public Library; Lian Partlow, Pasadena Museum of History; Susan Kim and G. Piper Carr, Corbis, Hearst Entertainment;

Jennifer Watts, Huntington Library and Valerie Schwan, Moving Image Archive, USC.

Research and Access: Gary Cowles on Busch Gardens; Dennis Crowley on the Dobbins Cycleway; John Harrigan, on Mount Lowe and Granite Gate;

Janet Kostner of the City of Pasadena, Film Permit Office; Robert Tanous, Vice Principal, Washington Middle School, Pasadena; and Bradley Williams

and Andrew Ballantyne, 9th Judicial Circuit Court of Appeals Historical Society. The project also benefited greatly from the walking tours conducted by

Pasadena Heritage; the volunteer docents are an invaluable source of information on the history of Pasadena and its built environment.

— The Labyrinth Project, May 19th, 2008

Rosemary Comella

Creative Director/Designer

Rosemary Comella has been working since 1999 as a project director, interface designer and programmer at the Labyrinth Project. As part of Labyrinth, she developed the interface for Tracing the Decay of Fiction, a cinematic-interactive project between experimental filmmaker Pat O'Neill and the Labyrinth team, and she collaborated on The Danube Exodus: The Rippling Current of the River, an interactive installation with filmmaker Peter Forgács that premiered at the Getty Museum in 2002. She also co-directed Bleeding Through: Layers of Los Angeles, an interactive installation and DVD-ROM, in collaboration with cultural historian Norman M. Klein, and with Andreas Kratky from ZKM. These three works were in the exhibition Future Cinema, a prominent and extensive survey of works using art and technology at ZKM in Karlsruhe, Germany. In early 2005, as part of series called Urban Traces, she completed Cultivating Pasadena: From Roses to Redevelopment an interactive exhibition, catalog and DVD-ROM that explores the evolving urban landscape through re-photography and oral history. She is currently working on another project in this series that further develops techniques for examining urban change, this time in an area of Los Angeles called Koreatown.

For the past twelve years, Comella has been producing new media works ranging from interactive installations and CD-ROMS with various artists to social research projects, childrens CD-ROMS and cultural projects. Some of the published CD-ROM titles she has been instrumental in developing include: An Anecdoted Archive of the Cold War by George Legrady and HyperReal Media Productions, San Francisco; Slippery Traces by George Legrady in collaboration with Rosemary Comella, published by ZKM, Karlsruhe; Clicking In by Lynn Hershman, published by Bay Press, Seattle; MUNTADAS: Media, Architecture, Installations, published by Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, and Cosmos, voyage dans luniverse, published by Montparnasse Multimedia, Paris. She has also participated in developing interactive museum installations for the following venues: Kunst und Austellung Halle Museum, Bonn; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; the Siemens Museum, Munich; the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles and ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe.

In 1998-99, before coming to the Labyrinth Project, Comella worked with Dr. Armando Valdez, a behavioral scientist and communications researcher who specializes in developing more effective methods and technologies for communicating to under served and hard-to-reach populations. For his company, Valdez & Associates, she designed and programmed the interface for an interactive kiosk disbursed to health clinics around California. This kiosk is a bi-lingual (Spanish/English) production meant to reach low-income, semi-literate women about the importance of the early detection of breast cancer. The results of the study of these kiosks demonstrated that interactive technology is an acceptable and effective medium for reaching the target audiences. Indeed the follow-up survey revealed that 51% of the non-adherent women in the sample obtained or scheduled a mammogram within four months after exposure to the intervention.

In addition to her career in the digital realm, Comella has also worked in the fine arts arena both as an assistant director at the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art and as an exhibiting artist in the San Francisco Bay Area." -- from Vectors, Volume 1, Issue 2, Spring 2006

1 COPY IN THE NEXT

Published in 2006 by Vectors in Volume 1, Issue 2.

This copy was given to the Electronic Literature Lab by Erik Loyer in November of 2021.

PUBLICATION TYPE

Online Journal

COPY MEDIA FORMAT

Web