Editor's Introduction

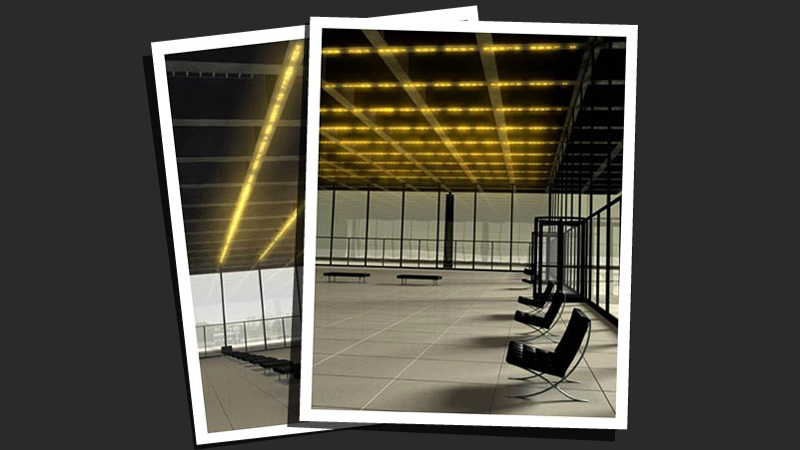

"Jenny Holzer's signature LED statements scroll past in an instant, commanding the reader's attention lest the moment be lost. These flickering screens are deeply meaningful experiments in time-based media, animating text long before the past decade's explosion of software packages made screen movement seem inevitable. They are also environmental media, specific to the places they inhabit; we might understand them as early investigations into ubiquitous computing, particularly given the labor-intensive programming required to realize any single LED work. Jenny Holzer at the Neue Nationalgalerie [is] a multi-perspectival documentation of a specific exhibition at a precise moment in space and time.

Combining video, animation, scholarly essays, photographs, and a wealth of other information, the project at one level functions as a multimedia catalog or database, deploying many forms of media to 'preserve' the inherently ephemeral experience of the art exhibition. This kind of 'thick description' allows multiple points of entry into both the Neue Nationalgalerie exhibit and into Holzer's work more generally.

But Jenny Holzer at the Neue Nationalgalerie does more than simply present evidence that this exhibition did indeed happen. Like all of the projects in this first issue of Vectors, it also implies an argument about the relationship between evidence and interface. In selecting what perspectives and artifacts would be included and in deciding how to structure access to these elements, the project privileges modes of presentation in dialogue with contemporary scholarship in performance studies, art history, and cultural studies. In detailing the sustained and collaborative labor involved in the construction of Holzer's LEDs, the piece reminds us of the often-invisible work that underlies our experiences of media and of art, something much less obvious to the visitors immersed in the dreamy modernists spaces of the original installation. In that regard, it shares with The Stolen Time Archive a precise goal: the desire to always remember the material in our engagements with the ephemeral." – Tara McPherson and Steve Anderson, Vectors Editors

Author's Statement

"Why

Jenny Holzer, why a retrospective at Berlin's Neue Nationalgalerie, why

an electronic journal, and why all three coming together in Vectors' inaugural issue devoted to 'evidence'? Framing an answer brings to mind some phrases from Holzer's signature early work, Truisms.

First: 'DESCRIPTION IS MORE VALUABLE THAN METAPHOR.' Like all of Holzer's

truisms, some rhetorical seduction and sleight-of-hand are at work here.

The phrase sounds so authoritative; it seems to compel assent; it must

be true. But what's the context? Is the statement really a

self-evident absolute truth; or is it only true in specific instances?

What is missing is deixis, the extralinguistic indication of

evidence that would allow you, the addressee of the phrase, to figure

out the reference, context, and truth-value of the supposed truism.

Seen

from one perspective, I think this truism actually says a lot about how

Gwen Allen and I, the organizers of this project, tried to proceed

methodologically. In the website, we place a premium on pointing. We

like the indexical gesture, the gesture that simply points at the

evidence and says to the reader: here is what it is, now you need to

contextualize it, to put your own signature on it. It also seems to us

that multimedia documentation is particularly useful for making an

indexical gesture. In lieu of having to use a 1000 words to describe a

picture of the Holzer installation, we can present a photograph,

animation, or video and then be able to say, 'here, take a look.'

But

there is, ultimately, a limit to the usefulness of just pointing. Or,

perhaps more precisely, there is a limit to the idea that one can simply

point and do nothing else. Basically, pointing presupposes framing.

Another way to say this is that description always implies metaphor, and

metaphor always implies description. One cannot describe without

selecting out certain things to describe. Description is always from a

perspective. As a result, it is always comparative to other

perspectives. Metaphor is comparison, and to the extent that any

pointing and describing requires a comparative theory for selecting what

to point at and describe, description entails metaphor. Pointing

already entails interpretation. Evidence is not simply what is seen;

evidence is what is pulled out of the whole field of the seen and shown

to be important. Ex + videre = out of + to see. Ironically, a 1000 words are sometimes more important than a single picture.

So

. . . in designing the Holzer site, we had to deal with the question of

how our pointing at and framing of evidence, i.e. our interface,

implies an interpretation of that evidence.

Another truism: 'A

SINGLE EVENT CAN HAVE INFINITELY MANY INTERPRETATIONS.' Again, we

tried to take this to heart. We asked a whole variety of contributors,

all from slightly different backgrounds, to offer different lenses on

how to perceive Holzer's work at the Nationalgalerie. And rather than

treat one lens as more important than another, we tried to be

egalitarian. Consequently our interface does not demand that a visitor

read one person's response before another. There is no single way that a

person has to go through the site. So while the use of multimedia

evidence allows us to privilege the gesture of pointing, the hyperlinked

structure of the web allows us to de-privilege a hierarchical structure

of argument.

But there is a catch to this truism as well.

Although a single event can have infinite interpretations, that does not

actually mean that each one of them is equally valid. I do believe

that all of the interpretations of Holzer's installation offered on our

site are valid and, perhaps, equally valid. But saying that does not

mean we were able to extricate ourselves from making some hierarchical

choices. There actually is a hierarchical organization implied in the

interface of our menu bar. One way to interact with the site is simply

to move progressively down the menu bar from the 'Home' to the 'Bibliography.' Doing so offers the visitor a more or less

chronological sense of how the installation at the Neue Nationalgalerie

was conceived, worked out in the planning stages, installed, received,

and finally archived. The web may aspire to be free-floating; the

interactivity of the web may aspire to put as much interpretive power on

the side of the receiver as on that of the sender; but there is

structure. The infinity of possible interpretations is a closed

infinity, rather than an open one.

And yet . . . 'DON'T PLACE TOO

MUCH TRUST IN EXPERTS.' Please do not think that a chronological

approach is an authoritative approach. As Gwen Allen makes clear in her

critical essay about the exhibition, digital technology in particular

and technologies of reproduction in general complicate the relative

natures of past, present, and future. That quasi-truism is one of the

theses about evidence that this site attempts to make manifest.

We

believe we've given you enough evidence to trust our interpretations.

Whether we have is, in the end, at least one interpretation left to you."

-- Ehren Fordyce, from Vectors, Volume 1, Issue 1, Fall 2005

Designer's Statement

"My goal as designer/programmer was to build a site that served as a virtual record, a interactive documentary snapshot, of Holzer's installation at the Berlin Neue Nationalgalerie. The site features a clean, functional interface that is both easy to use and attuned to Holzer's and Mies Van Der Rohe's modernist aesthetics. The site is also dynamically driven and therefore scalable; content can be modified, added or removed with relative ease as new information or scholarly research becomes available. -- Alessandro Ceglia

Alessandro was born in Milan, Italy and educated in the U.S. He received his B.A. from Dartmouth College in Art History and Asian Studies, and then spent five years abroad in various parts of Asia and Europe. He returned to the U.S. in 2001 to work as an interactive designer and developer. He is now based in Los Angeles, and continues to work on interactive projects while pursuing an M.F.A. in animation and digital art at USC's School of Cinema-Television." -- from Vectors, Volume 1, Issue 1, Fall 2005

Project Credits

"Installation Texts

Jenny Holzer

LED Engineering

Paul Miller

LED Programming

Merrick Ketcham

Initial Conception of the Web Project

Ehren Fordyce and Rebecca Groves

Principal Editors

Gwen Allen and Ehren Fordyce

Initial Web Design

Adrian Graham, with Aaron Russell

Flash Redesign and Development and Flash LED interfaces

Alessandro Ceglia

Overview, Architecture, Interview with Greg Niemeyer, and Critical Essay

Gwen Allen

Author's Statement and Geography

Ehren Fordyce

Animation

Ben Dean and Greg Niemeyer

Installation Photographs

Attilio Maranzano

Installation Video

Claudia Miller

Text on LED Installation

Merrick Ketcham

Exhibition Review

Daniel Mufson

With

special thanks to Jenny Holzer for permission to publish the

installation texts; to the Neue Nationalgalerie for their assistance in

providing photographs and video of the exhibition; and to Tara

McPherson, Greg Niemeyer, and Jeffrey Schnapp for their support in

developing the project.

This project was initially produced by

dpResearch with financial and technical support from the Stanford

Humanities Lab and the Stanford Department of Drama and additional

support from the Institute for Multimedia Literacy." -- from Vectors, Volume 1, Issue 1, Fall 2005

1 COPY IN THE NEXT

Published in Fall, 2005 by Vectors in Volume 1, Issue 1.

This copy was given to the Electronic Literature Lab by Erik Loyer in November of 2021.

PUBLICATION TYPE

Online Journal

COPY MEDIA FORMAT

Web